The Origins of Veterans Day

Nov. 11, 1918, Argonne Forest, France. Two long, snaking lines deep in the ground and filled with men can be seen stretching for miles on without end. In one trench was the Allies; in the trench opposite were the Axis Powers. And in between these lines of trenches was No Man’s Land. The sounds of artillery shells impacting the earth and the accompanying screams of men losing limbs and being sent flying from the impact can be heard on both sides. Rounds fired from rifles could still be heard ringing in the air right before penetrating the human body.

Soldiers were informed that an armistice, a cease fire, which would eventually lead to the Treaty of Versailles, was to go into effect at 11 a.m. that morning. Regardless of possessing that critical information, United States General John J. Pershing, Commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, ordered his troops to carry on as usual as if there was no armistice. The last American fatality of the First World War, the “war to end all wars,” was Sergeant Henry Gunther of A Company, 313th Infantry Regiment, 79th Infantry Division, who charged a German machine gun nest and, in the process, died from German machine gun fire at 10:59 a.m. Exactly within one minute to the ceasing of all hostilities.

That said, it is understandable that most Americans, especially those who have never served in the military, do not know the difference between Veterans Day and Memorial Day. Veterans Day is the day when the country comes together to honor the service of all Veterans, while Memorial Day is the day when the country comes together to remember and honor those who, as Abraham Lincoln once said, “gave the last full measure of devotion,” those individuals who paid the ultimate sacrifice in dying defending this country and the values that this country holds dear.

Originally, Veterans Day was known as Armistice Day to honor all those who served in the First World War, both living and dead; remembrance ceremonies were held on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month of the year – the exact day and time when the armistice went into effect starting with the declaration made by President Woodrow Wilson in 1919. Nonetheless, it was not until June 4, 1926, that the United States Congress passed a concurrent resolution (not a law) recognizing Armistice Day as a day of remembrance and calling on every U.S. president to declare such every year to the American people with the objective of not only honoring those veterans who served in the First World War, but to also recognize the fragility of peace.

That said, Armistice Day, despite being observed throughout the United States, was still not an officially recognized day of national remembrance. That would not happen until 12 years later, on May 13, 1938, with the passing of legislation 52 Stat. 351; 5 U. S. Code, Sec. 87a by the United States Congress marking Nov. 11th of each year an official national holiday of remembrance for those veterans who fought and died in the war to end all wars as well as the pursuit of peace in the world so as to prevent another tragedy like the First World War from happening again. Even so, that was not to be the case. The pursuit of peace would time and again have to be achieved through the use of violence via outright war. That statement may possible sound ironic and mybe even idiotic to some people, however, World War II was fought to stop Hitler and Nazi Germany from erasing the Jewish race and building an empire throughout Europe and beyond. Simultaneously, the same effort and sacrifice was made to stop the Japanese Empire from invading and expanding their control throughout Southeast Asia and the Pacific, such as the bombing of Pearl Harbor and what became known as the Rape of Nanking in China in 1939. Then there was the “Forgotten War,” the Korean War during which which not only Americans, but all countries that belonged to the United Nations fought to repel communist forces, both Korean and Chinese, from overtaking the entire Korean peninsula and forcing a sovereign people into a form of government they did not want. That said, World War II and the Korean War are far more nuanced than that and require more diligence at length. The point being that after World War I, world peace was not achieved.

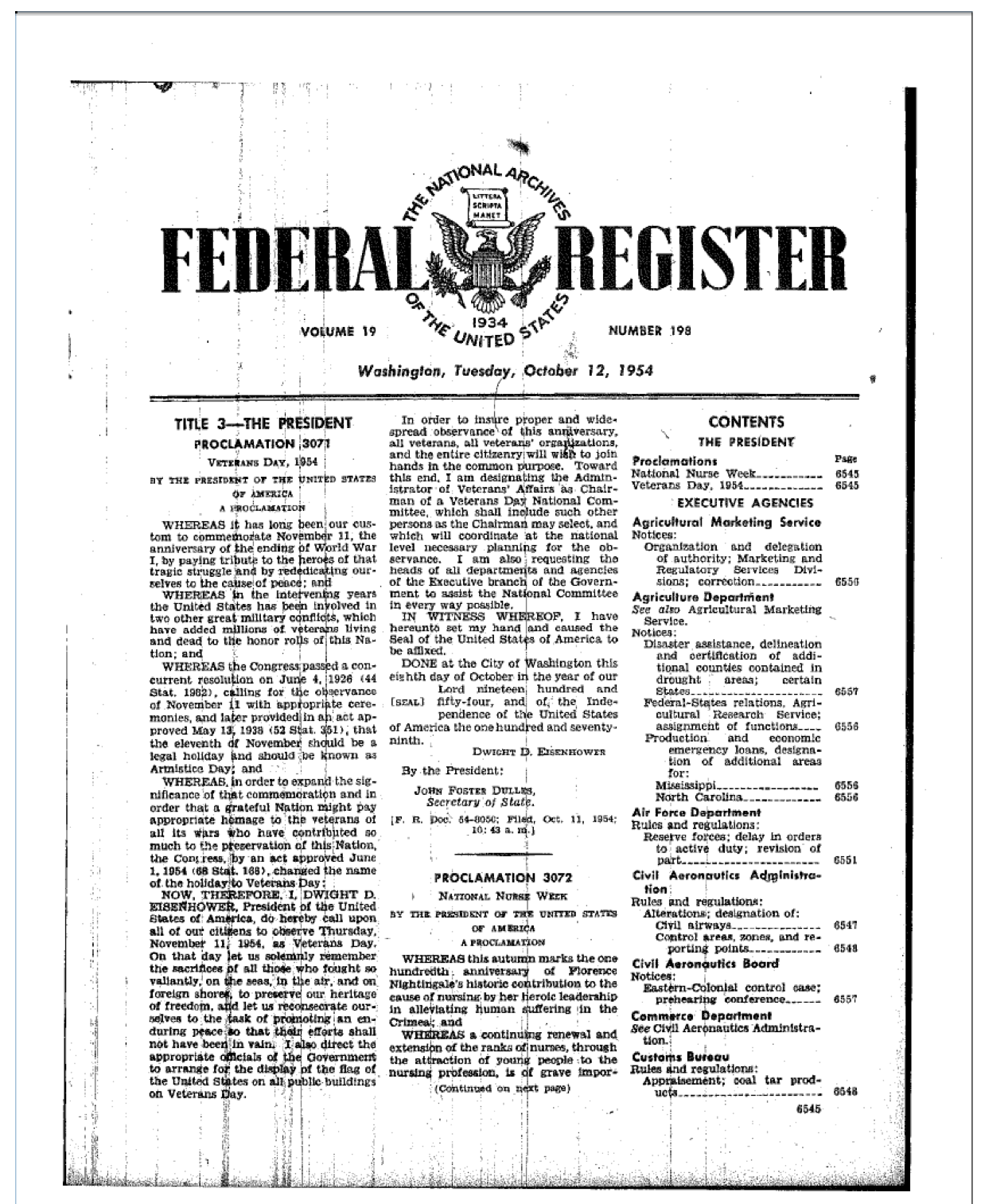

As such, several Veteran Service Organizations (VSO) lobbied Congress to amend 52 Stat. 351; 5 U. S. Code, Sec. 87a by replacing the word “Armistice” with “Veteran” whereby, rather than just observing a remembrance of those Americans who fought in World War I, that solemn day would be used as an occasion to observe and remember those veterans who served in all wars. This was achieved on June 1, 1954, with the passing of Public Law 380, which was followed by the first Veterans Day proclamation on Oct. 8, 1954, by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Ultimately, an additional legislation, which was passed by Congress to provide federal employees with a three-day weekend for certain national holidays such as Veterans Day, created confusion due to the day of observance being celebrated on a day other than Nov. 11th. Therefore, on Sept. 20, 1975, President Gerald R. Ford signed Public Law 94-97 (also known as 89 Stat. 479) into law, making Nov. 11 the officially nationally recognized day of observance and remembrance of all veterans who served, no matter if their service was in a time of peace or a time of war, because the true observance is of those who swore an oath to the U.S. Constitution to “preserve and defend the Constitution of the United States,” even if it meant giving this country and her people the ultimate sacrifice.